Ware wa umi no ko

Ware wa umi no ko, shiranami no

Sawagu isobe no matsubara ni

Kemuri tanabiku tomaya koso

Waga natsukashiki sumika nareUmarete shio ni yuami shite

Nami wo komori no uta to kiki

Senri yosekuru umi no ki wo

Suite warabe to narini keriTakaku hanatsuku isono ka ni

Fudan no hana no kaori ari

Nagisa no matsu ni fuku kaze wo

Imijiki gaku to warewa kikuLyricist:MIYAHARA Kouichirou

Supplementary Lyricist:HAGA Yaichi

Composer:Unknown

in 1910

I am a child of the sea

I am a child of the sea,

In the pine forest on the side where white‐crested waves hit hard

The poor house where the smoke of cooking stands

It is my nostalgic house

I was born and washed my body in the sea water

The sound of the waves was a lullaby substitute

The power of the sea coming from the other side of a thousand miles

I spent my childhood while sucking in my heart

In the smell of a shore reef that stimulates the nose intensely

It smells like a flower that never dies

Wind blowing in the pine forest

I hear that it looks like a great music

Historical Origins and Publication

In 1910, following the conclusion of the Russo-Japanese War, the beloved children’s song “Ware wa Umi no Ko” (I am Child of the Sea) was first published in “Jinjou shougakkou tokuhon shouka,” an official songbook designed for elementary school students of that era. This publication marked the beginning of what would become one of Japan’s most enduring and musical heritage, capturing the essence of Japan’s deep connection to the sea.

The song emerged during a period of significant national transformation, when Japan was establishing itself as a modern maritime power. The timing of its publication was particularly meaningful, as it reflected the country’s growing awareness of its oceanic identity and the importance of maritime culture in shaping the Japanese national character. The song quickly gained popularity in schools across the nation, becoming an integral part of children’s musical education and cultural heritage.

Russo-Japanese War (Public Domain)

The Mystery of Authorship

Due to the educational policies of the Meiji era Ministry of Education, which deliberately concealed the identities of authors to maintain the perceived objectivity of educational materials, “Ware wa Umi no Ko” was officially classified as “author unknown” for many decades. This anonymity shrouded the song in mystery and contributed to its folk-like quality, as it seemed to emerge organically from Japanese culture itself.

However, this mystery was eventually solved during the Heisei era (1989-2019), when compelling evidence emerged pointing to the song’s true creator. Based on artifacts and documentation presented by surviving family members, scholarly consensus now widely accepts that the lyricist was MIYAHARA Kouichirou, a poet and educator of the Meiji period. This revelation added a human dimension to the song’s history while highlighting the collaborative and often anonymous nature of Japan’s cultural creation during the early modern period.

Cultural Significance and Maritime Identity

The song stands as a vivid and poetic portrayal of a young boy born and raised in a traditional Japanese fishing village, embodying the robust physical strength and resilient spirit that characterizes Japan as a quintessential maritime nation. The lyrics paint a picture of coastal life that resonated deeply with the Japanese experience, celebrating the connection between the people and the sea that surrounds their island nation.

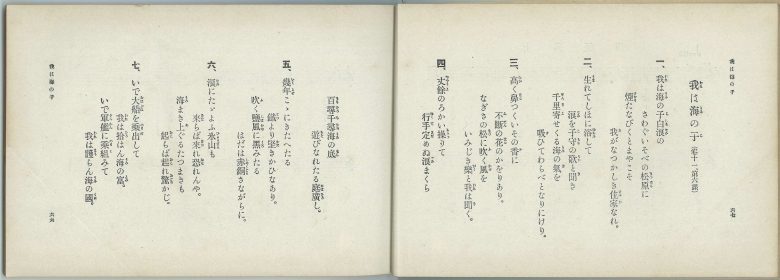

Originally, the complete song consisted of seven verses, with verses four through seven depicting the protagonist’s evolution into a military serviceman actively serving on the seas. These later verses reflected the militaristic spirit of early 20th-century Japan and the importance of naval power in the nation’s identity. However, following Japan’s defeat in World War II, these martial verses were removed by the General Headquarters (GHQ) of the Allied occupation forces as part of the broader demilitarization efforts.

The song subsequently disappeared from school textbooks for an extended period, not only due to its military associations but also because its classical Japanese wording had become increasingly difficult for modern children to comprehend. The language gap between Meiji-era Japanese and contemporary speech patterns made the song less accessible to new generations. It wasn’t until 1958 that “Ware wa Umi no Ko” was officially restored to educational curricula, though only the first three verses were reinstated, focusing on the innocent portrayal of coastal childhood rather than military themes.

Japan’s Oceanic Geography and Enduring Legacy

Japan’s profound connection to the sea, as celebrated in this song, is rooted in remarkable geographical facts. According to the 2004 edition of Japan’s official “Coastal Statistics,” the nation boasts a coastline stretching 35,297 kilometers, ranking as the sixth longest in the world. This extensive maritime boundary is made even more remarkable by Japan’s unique geographic position, spanning from subarctic regions in the north to subtropical zones in the south, creating an extraordinary diversity of oceanic landscapes and marine ecosystems.

This geographical diversity manifests in stunning contrasts: from the drift ice seas of Hokkaidou, where ice floes create ethereal winter seascapes, to the vibrant coral reefs of Okinawa, where tropical fish display brilliant colors in crystal-clear waters. Each region offers distinct marine environments that have shaped local cultures, traditions, and ways of life. Japan’s renowned food culture owes much to these oceanic riches, with each coastal region developing unique culinary traditions based on local seafood specialties. When visitors explore fishing villages throughout Japan, they encounter an incredible variety of distinctive marine products, from Hokkaido’s sea urchin and crab to Kyushu’s yellowtail and sea bream.

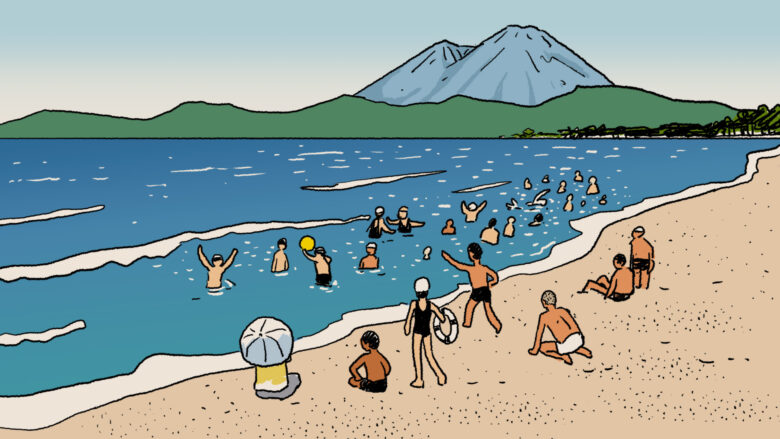

Fishing Village

Despite the passage of more than a century since its creation, “Ware wa Umi no Ko” continues to touch hearts with its plaintive melody and evocative lyrics that capture the essence of Japan’s maritime soul. The song’s enduring appeal and cultural significance were formally recognized when it was selected as one of the prestigious “100 Best Japanese Songs,” cementing its place in the nation’s musical heritage. Today, it serves not only as a nostalgic reminder of Japan’s coastal traditions but also as a bridge connecting modern Japanese people with their maritime roots and the timeless relationship between the Japanese people and the sea that has shaped their civilization for millennia.

*MIYAHARA_Kouichiro, who wrote the lyrics, was born and raised near Sakurajima, Kagoshima Prefecture.

コメント

What’s up to every , as I am actually keen of reading this webpage’s post to be updated daily.

It contains pleasant material.