Omatsuri mambo / Episode 1: The Uncle from Kanda

Watashi no tonari no ojisan wa

Kanda no umare de chakichaki edokko

Omatsuri sawagi ga daisuki de

Nejiri hachimaki soroi no yukata

Ame ga furou ga yari ga furou ga

Asa kara ban made omikoshi katsuide

Wasshoi wasshoi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Keiki wo tsukero shio maite okure

Wasshoi wasshoi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Sore soresore omatsuri daOjisan ojisan taihen da

Dokoka de hansho ga natte iru

Kaji wa chikai yo suriban da

Nani wo ittemo wasshoi shoi

Nani wo kiitemo wasshoi shoi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Sore soresore omatsuri daLyricist & Composer:HARA Rokurou

in 1952

My friendly neighbor, the uncle

Was born in Kanda, a true Edokko

He loves the festival excitement

Wearing a twisted headband and matching yukata

Whether it rains or spears fall from the sky

From morning till night, he carries the mikoshi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Bring in the cheer, sprinkle the salt

Wasshoi wasshoi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Sore soresore, it’s the festival

Ojisan! Ojisan! There’s an emergency!

Somewhere the fire bell is ringing

The fire is close, it’s a fire watch

No matter what you say, wasshoi shoi

No matter what you hear, wasshoi shoi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Wasshoi wasshoi

Sore soresore, it’s the festival

The song “Omatsuri Mambo” opens briskly with a rhythmic, upbeat mambo beat. The protagonist is a stylish uncle born and raised in Kanda—a true Edokko, a native of Edo (old Toukyou(Tokyo)), and a genuine Kanda native.

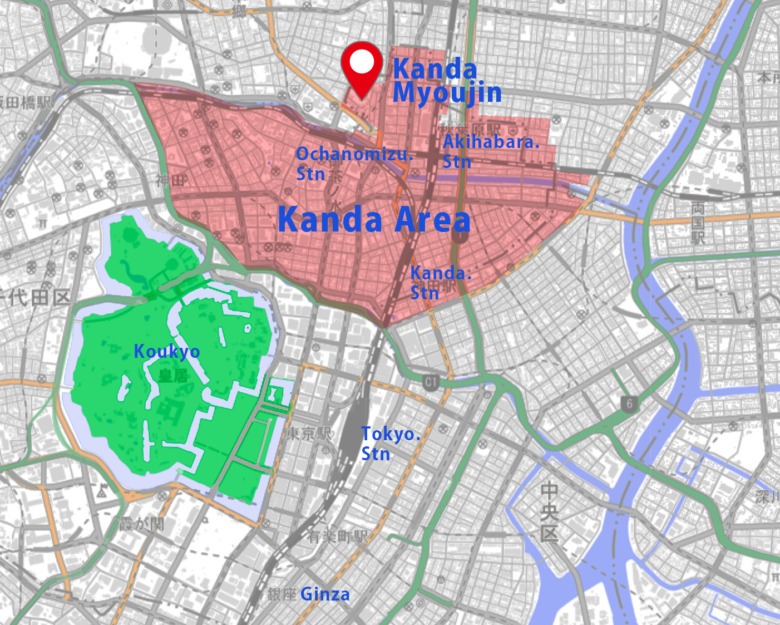

Kanda is located in the heart of Toukyou(Tokyo), in Chiyoda Ward. Today, it’s known as an area that includes Akihabara, the world-famous electronics district and subculture mecca. However, historically, it developed as a prestigious merchant and artisan district centered around Kanda Myoujin Shrine, which guards the northeastern direction (the “demon’s gate”) of Edo Castle. This vibrant neighborhood buzzed with merchants and craftsmen exchanging spirited calls. For those born and raised here, festivals run through their very blood.

Kanda myoujin, formally known as Kanda Shrine, has been beloved by common people since the Edo period as the general guardian shrine of Edo. The deities enshrined there are Oonamuchi-no-mikoto (Ookuninushi-no-mikoto, Daikoku-sama), Sukunahikona-no-mikoto (Ebisu-sama), and Taira no Masakado. The shrine is particularly known for enshrining Taira no Masakado and has been revered as Edo’s guardian deity. Every May, the Kanda Festival is held with great pageantry, and as one of Edo’s three great festivals, it continues to captivate many people to this day.

Base map: GSI Tiles (Standard Map), Geospatial Information Authority of Japan (GSI), modified.

Fans of period dramas will immediately think of “Zenigata Heiji” when they hear Kanda myoujin. The detective Zenigata Heiji lived precisely at the foot of Kanda myoujin. The Kanda tenement houses where his assistant Hachigoro would come running, crying “Boss!”—and from which Heiji would throw his trademark copper coins—Kanda is truly a place that symbolizes Edo’s common people’s culture.

The uncle, who grew up in this Kanda, has been wearing festival jackets and carrying portable shrines (mikoshi) since he was old enough to understand. Carrying a mikoshi is not merely a ritual—it’s an identity and a source of pride for a Kanda native. The moment when hundreds of carriers unite with the chant “Wasshoi, Wasshoi” to hoist up the heavy mikoshi, the uncle’s face flushes and his eyes shine like a boy’s.

To carry a mikoshi means to bear the portable shrine containing the divine spirit of Kanda myoujin and transport the deity throughout the town. The deity makes a circuit of the parish where the worshippers live, bestowing blessings upon the people. The carriers protect and worship the deity, deepening bonds with their neighborhood comrades and passing down the soul of Kanda to the next generation. This is not merely a traditional event but a living faith and a sacred ceremony that confirms community solidarity.

There’s something called the “shitamachi spirit”—the spirit of downtown Toukyou(Tokyo). It embodies the Edokko aesthetic of “not keeping money overnight” and values “iki” (sophisticated style) above all else. Don’t sweat the small stuff; live the present moment to the fullest. Lend a hand to those in trouble, and loosen the purse strings when festival time comes. This generous spirit is the essence of a Kanda native.

Directed by Keigo Kimura, produced by en:Daiei Film – Screenshot of the movie, public domain, by link

The phrase “Shio maite okure” (sprinkle the salt) that appears in the lyrics is also intriguing. Rather than being for fire prevention, it can be interpreted as purifying salt for the sacred festival. In Shinto tradition, salt has been believed to have the power to dispel impurity and create sacred space. Before or during a festival, which is a sacred event, salt is scattered to purify the area. This is a reverent preparation for welcoming the deity. The uncle, too, was one of those devout Edokko who valued such purification rituals.

That’s why, once the festival begins, the uncle forgets all mundane concerns. Work, household matters, even tomorrow—all are set aside as he immerses himself completely in the festival. A neighbor seems to be shouting, “Uncle, it’s terrible! There’s a fire!” but amid the weight of the mikoshi and the cheers, such voices fade into the distant beyond.

Background: “Meguro Gyounin-zaka Fire Scroll”,

National Diet Library Digital Collections (public domain, Japan)

Here, the term “suriban” deserves attention. This is an abbreviation of “suri-hanshou” (rubbing half-bell), meaning to ring the half-bell (hanshou) repeatedly to warn of a nearby fire, or the sound itself. Normally, the half-bell would be struck slowly—”kaan, kaan”—but when fire was approaching, it would be rung continuously, almost frantically, as if rubbing it. That urgent sound was an emergency alert to which everyone should have paid attention. But for the uncle, lost in the festival, even that couldn’t reach his ears.

Edo and fire have an inseparable relationship. As the saying goes, “Fires and fights are the flowers of Edo”—the city was frequently struck by conflagrations. The reason was that most of Edo’s buildings were wooden structures. Densely packed tenement houses, wooden shops, temples and shrines—once a fire started, it would spread in an instant, becoming a major disaster. The Great Meireki Fire of 1657 consumed most of Edo and is said to have claimed over 100,000 lives.

Hanshou

Due to this constant danger of fire, Edo residents developed a unique attitude toward conflagration. Since everything could be lost to fire at any moment, perhaps this gave birth to the aesthetic of “not keeping money overnight.” Even if you accumulated wealth, it could turn to ash in a single night. In that case, why not enjoy life in the present? Such was their philosophical resignation.

The mikoshi parading through Kanda’s streets, the cheers from the roadside, the sounds of festival music—everything blends together, drawing the uncle into the vortex at the festival’s heart. The weight of the mikoshi digging into his shoulders, the sweat streaming down like a waterfall—all of it feels pleasant. Having entered the ecstatic state of a mikoshi bearer, the uncle can no longer hear anything. Tomorrow? Who cares! This moment, carrying the mikoshi—that alone is the uncle’s entire world.

The rhythmic mambo beat perfectly expresses the uncle’s elated spirit. The light tempo, the cheerful melody—listeners can’t help but sway along. This is the very embodiment of festival euphoria.

コメント